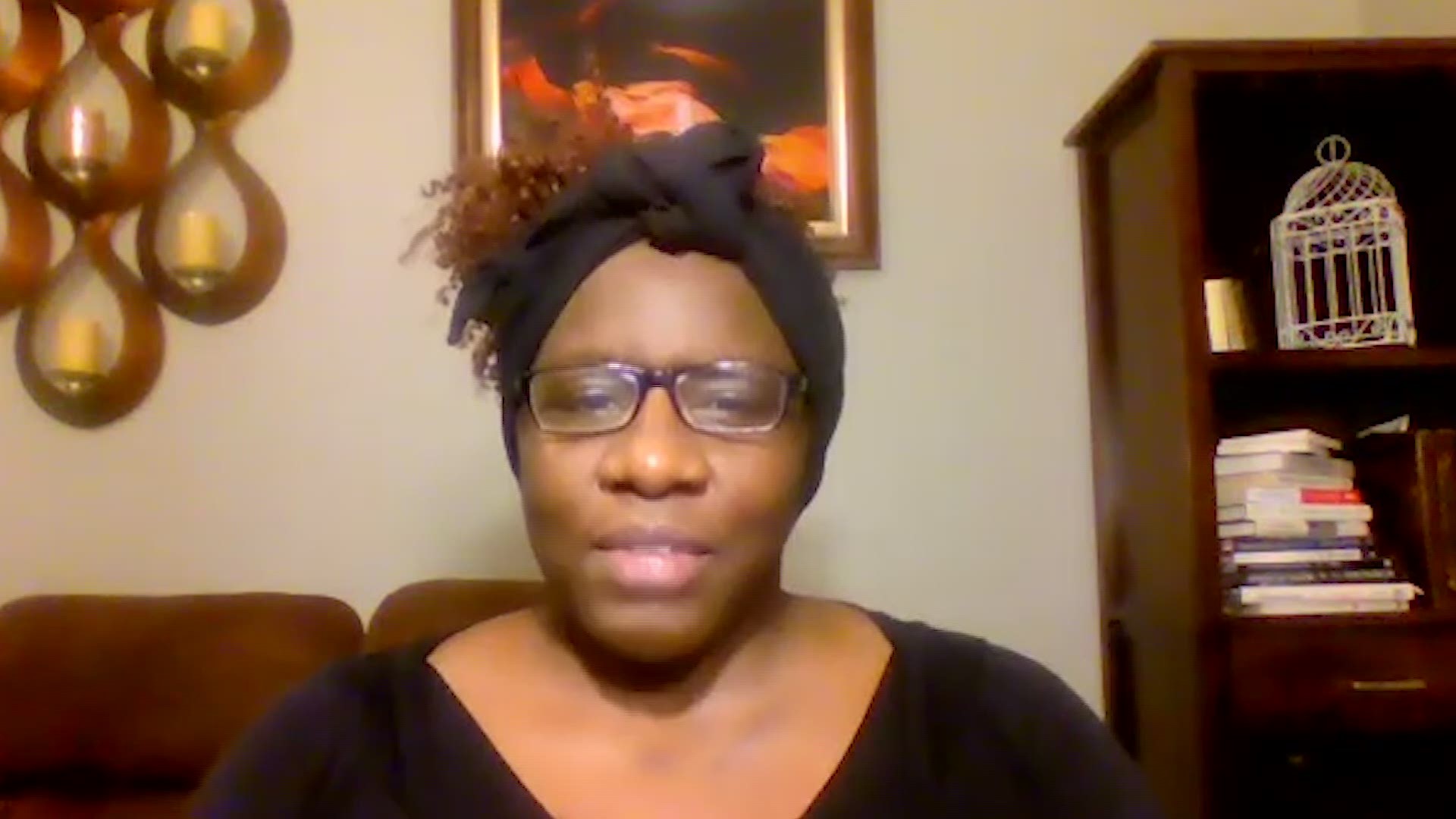

BUFFALO, N.Y. — When Keesha Lawson was asked how she felt about the coronavirus vaccine, she firmly expressed her uncertainty.

"It just doesn’t make me feel comfortable. It doesn’t make me feel at ease", she said.

While Lawson is happy there is a vaccine option, she's not sure about efforts to ensure the vaccine makes its way into communities of color. She told 2 On Your Side's Karys Belger the speed with which the vaccine was produced is one reason why she's not sure she will get the vaccine when the opportunity comes. The other reason has to do with the historical mistreatment of people of color.

"Given the history of the public health system with regard to people of color’s health, I’m just not sold," she told 2 On Your Side.

Lawson is not alone in her skepticism. A study by the Pew Research Center showed only 41 percent of African Americans nationwide would get the vaccine.

Henry-Louis Taylor, a professor at the University at Buffalo told 2 On Your Side, he's heard similar hesitations from people he's spoken to and the reasons are valid.

"Historically, African Americans have been victimized by the medical industry. Many people are aware of the Tuskegee Syphilis experiments. There were efforts made to sterilize black women without their knowledge, he told 2 On Your Side.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study took place from 1932 until 1972 and was conducted by the United States Public Health Service and the Centers for Disease Control. During the study, 600 men were chosen. 399 had latent syphilis and 201 were not infected. The men were promised free medical care, but were not informed of their diagnosis and were treated with ineffective measures and disguised placebo medication. The purpose was to see the effect of untreated syphilis in African American Men. 128 participants died either as a result of syphilis or complications caused by it.

As desegregation began in the United States, attempts were made to control the black population and the populations of other minority and poor communities. The result was the forced sterilization of thousands of women. The practice continued into the late 20th century.

Taylor, who also works with the Health Equity Taskforce, told 2 On Your Side stories of these events have been repeated and passed down in communities of color, sowing seeds of mistrust in medical professionals.

He also says the situation has been exacerbated by the social determinants of health that already exist like lack of access to regular healthcare and a healthy diet. He specifically pointed out that many black and brown neighborhoods in Buffalo are located in food deserts.

When asked what it would take to get people to trust in the vaccine, Taylor told 2 On Your Side's Karys Belger, having people who are familiar with the area and truly know the people bring in the medical experts would be a start. He explains, these are the people who already have established trust with the community.

"This is why the leaders of that community are the ones that stand forward."

Lawson said this tactic would make her feel better about the vaccine but she most likely would not get it until someone very close to her told her it was safe.

"My next-door neighbor you know, telling me that they got it and later they’re still feeling fine. That’s what makes us feel comfortable."