MONTGOMERY, Ala. — Alabama has moved out of the bottom three in the national rankings for preterm birth rate, less for improvement within the state than worsening outcomes elsewhere.

Data from the March of Dimes shows Alabama’s preterm birth rate decreased from 13.1% in 2021 to 12.8% in 2022. Although the rate ticked up slightly to 12.9% in 2023, Honour Hill, director of maternal and infant health initiatives for March of Dimes in Alabama, described the increase as statistically insignificant, suggesting Alabama may have followed a national trend of not necessarily improving but not getting worse either.

“When we look from 2013 to 2023, (the preterm birth rate has) gone significantly up, but we’re seeing ourselves kind of sit at right underneath 13%. So it’s a little bit of us getting better in the last couple of years, but a lot of it is going to be some of those other states getting worse,” she said.

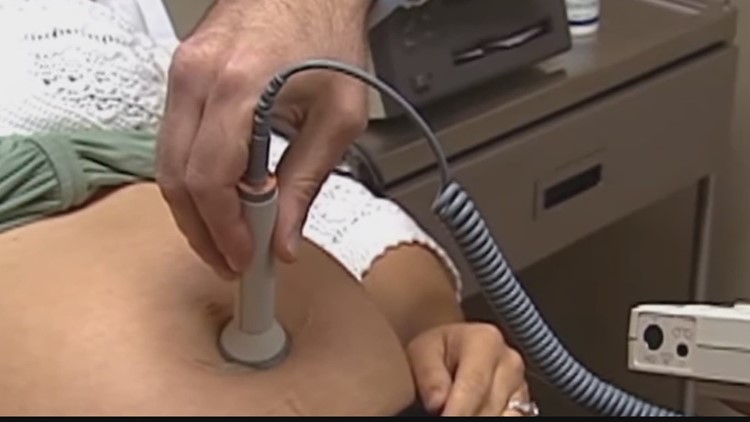

According to the March of Dimes, 143 of the 1,112 babies born on average each week in Alabama are born preterm, defined by the CDC as births that happen before 37 weeks of pregnancy. Of those, 22 babies a week are born “very preterm,” or under 35 weeks gestation. The earlier a baby is born, the higher the risks for breathing problems, feeding difficulties, cerebral palsy, developmental delay, or vision and hearing problems.

Dr. Wes Stubblefield, the district medical officer at the Alabama Department of Public Health, said that year-to-year changes in infant mortality data are influenced by population size and data variability.

“The larger the data set, the more reliable the information. It’s the same with counties. The graph for the entire US is much smoother than Alabama’s when comparing year-over-year trends,” he said.

Alabama’s infant and maternal care is filled with disparities between whites and marginalized groups, and preterm birth rates are no different. According to Hill, Black families in Alabama face a preterm birth rate of 15.9%, while Asian American and Pacific Islanders report the highest rate at 17.3%.

Although Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders only make up 0.1% of the population in Alabama, Hill said it’s important to break down data by specific racial and ethnic groups to better understand and address disparities. Pacific Islanders’ high preterm birth rates are statistically significant, she said, underscoring systemic inequities.

“We need to ask these communities directly what they need to thrive, rather than assuming one-size-fits-all solutions,” she said.

Dr. Christopher Zahn, chief of clinical practice and health equity and quality at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), said in a statement the organization is committed to its efforts to address racial inequities in maternal and infant health outcomes, particularly focusing on reducing the rates of preterm birth.

“One of ACOG’s longstanding policy priorities has been to extend postpartum Medicaid from 60 days after delivery to one year. Because Medicaid pays for roughly 64% of births to Black women, extending this coverage is key to helping reduce disparities but especially racial health disparities,” Zahn said.

In March 2023, the Alabama Medicaid Agency received approval from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to extend postpartum Medicaid coverage from 60 days to a full year. Medicaid pays for more than half of the births in Alabama.

ACOG is also pushing for more investment in maternal and infant health research, with an emphasis on enhancing diversity in clinical studies.

“ACOG endorses and advocates for the swift passage of the PREEMIE Reauthorization Act, which would renew the federal government’s commitment to research and programs on preterm birth, reauthorize activities aimed at preventing preterm birth, and provide for a new study on the costs, impact of social factors, and gaps in public health programs that lead to prematurity,” Zahn said in the statement.

One key factor linked to poor birth outcomes is inadequate prenatal care. Hill said Alabama’s rate of inadequate prenatal care, defined as the percentage of women who get fewer than half of the appropriate medical appointments during a pregnancy, stands at 18.1%. That’s higher than the national average of 15.7%. She said that maternity care deserts, particularly in rural areas, compound this issue.

“Access to care is crucial,” Hill said. “In counties with full maternity care access, we still see barriers like transportation, familial support, and economic challenges that prevent women from receiving adequate care.”

The March of Dimes, for the first time, examined how environmental factors like extreme heat and air pollution contribute to adverse birth outcomes, highlighting disparities among different demographics. For instance, Black and Hispanic populations experience 56% and 63% higher pollution exposure, respectively, compared to white populations.

“We are seeing a lack of air quality sensors, and we’re also looking at that extreme heat, making sure that our air pollution and those sorts of things are being looked at for the benefit of pregnant women,” Hill said.

According to a May 2024 Journal of the American Medical Association study, extreme heat events can affect perinatal health, with preterm and early-term birth rates increasing after heat waves, particularly among socioeconomically disadvantaged subgroups.

Both Hill and Stubblefield underscored the need for targeted interventions to reduce disparities.

“Significant disparities still exist, and reducing Alabama‘s infant mortality rate continues to be a top priority for multiple different agencies in the state including ADPH,” Stubblefield said.

This article originally appeared in the Alabama Reflector, an independent, nonprofit news outlet. It appears on FOX54.com under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.