HUNTSVILLE, Ala. —

KEY CONCEPTS

Conditions that trigger fall color each year are shifting with climate change, potentially impacting the ecological and economic value linked to fall foliage.

The timing and brilliance of fall color are influenced by temperature, day length, and rainfall — as well as other conditions including extreme weather events.

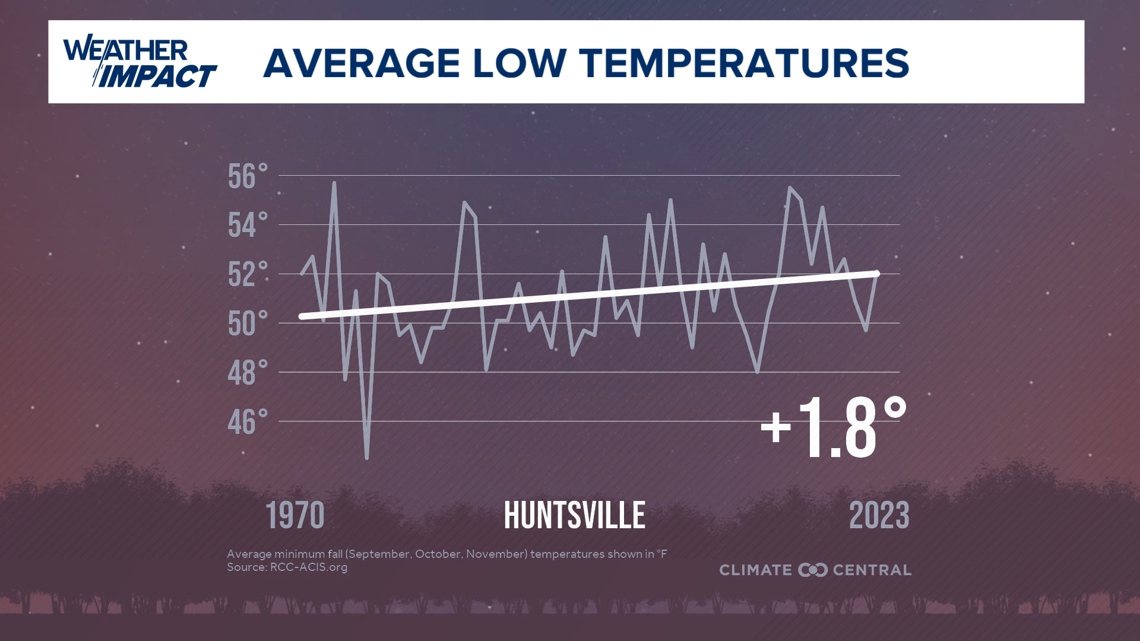

Cool nights are one of several factors that promote colorful leaves. But fall nights have warmed in 212 U.S. locations — by 2.7°F on average from 1970 to 2023.

As the fall season progresses, cooler temperatures trigger plants to start shutting down. Warmer fall temperatures can disrupt or delay these cool cues and lead to later and shorter peak fall foliage.

But fall plant cycles are complex and vary across tree species and regions. And observations show both earlier and later shifts in the timing of peak fall foliage in recent decades.

Although observed trends vary, our understanding of the mechanisms behind leaf fall is growing.

Understanding these cycles is important — especially as we increasingly rely on forests to soak up excess carbon pollution from the air in an effort to slow climate change.

Golden aspen groves in the Rockies. Orange sassafras slopes along the Blue Ridge Parkway. Scarlet maples dotting New England’s lakeshores.

As leaf-peeping season spreads across the U.S. each fall, it brings billions of dollars in tourism to some states. The fall display also signals the end of the growing season — a critical time for forest ecosystems.

But the conditions that trigger fall color each year are shifting with climate change, potentially disrupting the ecological and economic value linked to fall foliage.

Plants use cues from their environment to time life cycle events. For trees that shed their leaves in the fall, three key factors affect the timing, duration, and brilliance of fall color:

Shorter day length: As days shorten during fall, the reduced daily sun exposure cues plants to ramp down photosynthesis. This process reshuffles leaf pigments and kicks off the colorful displays of fall. At a given latitude and time of year, day length remains constant as the climate warms.

Temperature: As the fall season progresses, cooler temperatures trigger plants to start shutting down. But widespread fall warming delays these cool cues and generally (though not always) leads to later and shorter peak fall foliage periods. See below for more on the complex effects of climate warming on fall color.

Rainfall: Adequate summer rain and soil moisture can cause later, brighter color. But too little or too much rain can both stress trees and cause leaves to drop early. Precipitation extremes are likely to become more common as the climate warms, which could impact fall foliage displays.

Trees are sensitive to these three factors, but that’s not all. A wide range of other climate conditions (which vary across tree species and regions) can also influence the timing, duration, and color of peak fall foliage. Here are a few:

Shorter fall days cue plants to ramp down photosynthesis for the season. This reduces chlorophyll (a green pigment used during photosynthesis), revealing orange and yellow leaf pigments that were previously masked by green. At this stage, some species (such as red maples) start producing red or purple pigments, enhancing the vibrance of fall forests.

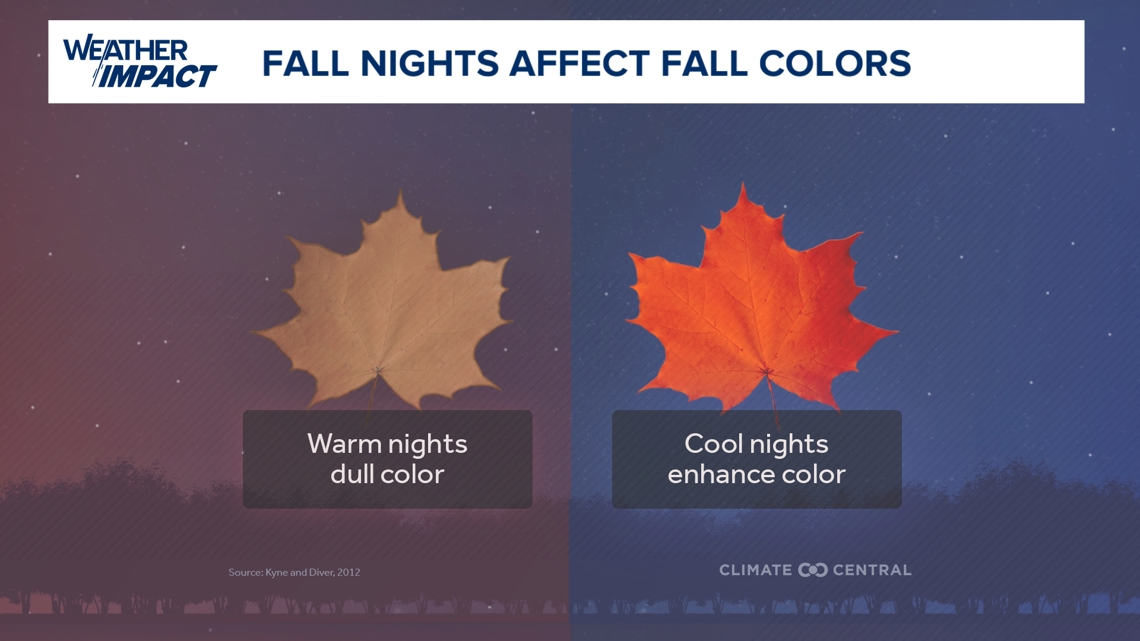

Cool nights and bright, sunny days can enhance vivid color displays, which favor a 9°F to 12°F difference between daytime and nighttime temperatures. But the cool nights that help create colorful leaves are becoming less common. According to Climate Central analysis, fall nights have warmed in 212 (87% of 243 total) U.S. locations analyzed — by 2.7°F on average from 1970 to 2023.

Early frost can damage leaves and limit production of red pigments.

Severe drought and extreme heat can stress trees so that their leaves shrivel and turn brown before producing a colorful display. Many U.S. locations have experienced longer heat streaks and rising drought risks with warming.

Diverse forests generally have longer and more brilliant fall color displays as different species change color at different times. The composition of North American forests could change in response to climate change, however, which could in turn affect fall displays.

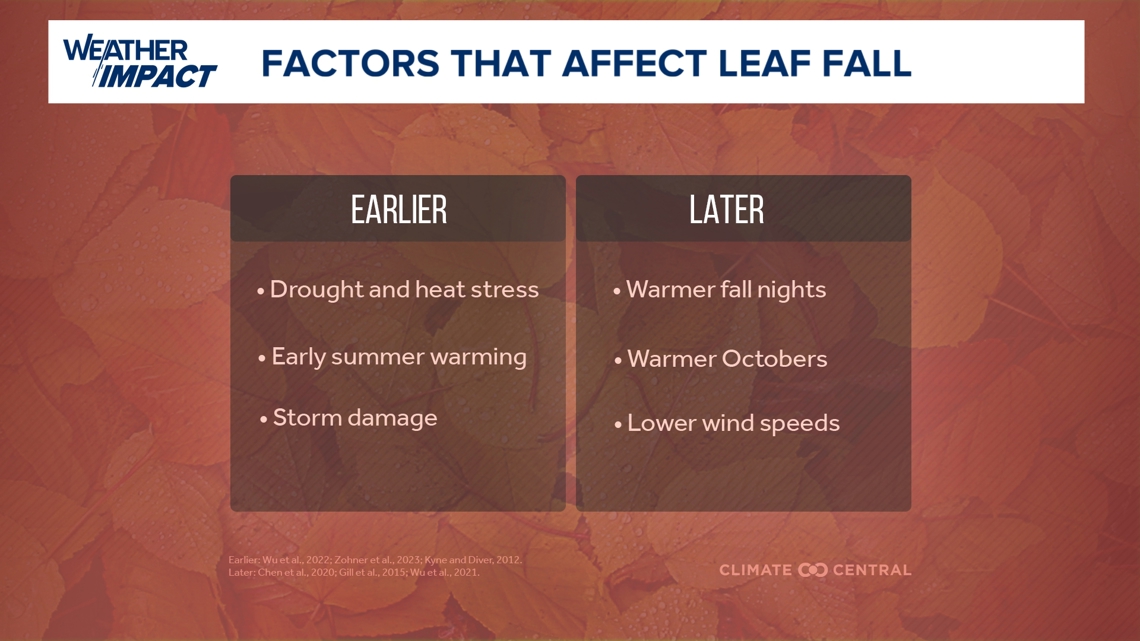

Warming fall nights can contribute to a delayed start of leaf color and drop. According to Climate Central analysis, fall nights have warmed in 212 (87% of 243 total) U.S. locations analyzed — by 2.7°F on average from 1970 to 2023.

Higher October temperatures were most strongly linked with later leaf fall in the Northern Hemisphere. October warming comes along with fall warming observed across the U.S.

Declining winds can lead to later leaf fall in higher latitudes (>50°N).

Lower latitudes (25°N to 40°N), where days are longer, are generally more sensitive to the effects of warming temperatures than to the effects of shorter fall days and tend to experience delayed leaf fall with warming.

Artificial night light from cities and other developed areas can delay fall color, although the impact is complex and likely also depends on temperature.

Early summer warming can lead to earlier fall color. According to a 2023 study, warmer temperatures prior to the summer solstice boost growing season activity and lead to earlier leaf shut-down in northern forests.

Drought and water stress can trigger earlier shedding of leaves. Warmer fall days can contribute to drought stress and earlier leaf fall.

More fall chill, or cumulative exposure to fall temperatures below 68°F, was significantly linked with earlier leaf fall in temperate Northern Hemisphere locations.

Higher latitudes (50°N to 70°N) are generally more sensitive to day length than other climate factors and tend to experience earlier leaf fall. In higher latitudes, where day lengths are shorter, plant cycles are generally more sensitive to the effects of shortening day lengths each fall than to the effects of temperature.

Severe drought can stress plants and cause them to drop their leaves early, shortening colorful displays or even causing leaf drop before colors appear. Damaging droughts are likely to intensify with climate warming, especially in the western U.S.

Extreme heat can also stress trees and shorten displays. As the climate warms, summer heat stress could lead to shorter fall color displays for many tree species.

Heavy storms and rains can physically knock leaves off of trees before they change color. Climate change is bringing heavier rainfall extremes.

Wildfires burn trees and leaves, draining forests of fall color. And wildfire seasons are lengthening and intensifying across the U.S., particularly in the west.

If the long list of factors above gives the impression that fall plant cycles are complex, that’s because they are. Some other seasons are better understood.

For example, earlier leaf emergence in the spring is a broadly-observed response to warming winters. By comparison, the effects of climate change on fall foliage are more variable and less understood.

Autumn has even been called “the neglected season in climate change research.” But this is an active area of research and our knowledge is growing.

While some studies observe a delay in fall leaf color of several days per decade in the U.S., others find an earlier onset of leaf color, and still others indicate no significant change in the timing of leaf color in Europe from 1982 to 2011.

Although observed trends vary, our understanding of the mechanisms behind leaf fall is growing. For example, a 2023 study found that warmer temperatures prior to the summer solstice boost plant productivity and can lead to earlier leaf shut-down in northern forests — about 2 days earlier per 1°C (1.8°F) of pre-solstice warming.

Understanding these cycles and their response to climate change is important — especially as we increasingly rely on forests and other ecosystems to soak up excess CO2 from the air in an effort to slow climate change. The timing of fall leaf drop partly determines the length of time that plants have to grow and take up carbon pollution each year.